"Instrumentum laboris' calls for welcoming Church that embraces diversity"

By Salvatore Cernuzio

A document of some sixty pages that incorporates the experiences of local Churches in every region of the world – Churches that are experiencing wars, climate change, economic systems that produce “exploitation, inequality, and ‘waste’.” Churches whose faithful suffer martyrdom, in countries where they are minorities or where they are coming to terms “with an increasingly driven, and sometimes aggressive, secularisation.” Churches wounded by sexual abuse, or abuses of power and conscience,” whether economic and institutional – wounds that demand answers and “conversion.” Churches that are fearlessly confronting the challenges by engaging in the synodal discernment, without trying to “resolve them at all costs”: “Only in this way can these tensions become sources of energy and not lapse into destructive polarisations.”

Released on Tuesday morning, the document – known as the Instrumentum laboris – will be the basis for the work of the participants in the General Assembly of the Synod on Synodality, which begins in the Vatican in October 2023 and concludes with a second Assembly one year later.

Deliberately conceived as a starting point and not a point of arrival, the Instrumentum laboris brings together the experiences of dioceses around the world over the last two years, starting from 10 October 2021, when Pope Francis set in motion a journey to discern what steps to take “to grow as a synodal Church.” The Instrumentum laboris, therefore, is intended as an aid for discernment “during” the General Assembly, while at the same time serving as a means of preparation for participants as it looks ahead to the gathering. “Indeed, the purpose of the synodal process” the document states, repeating the words of the earlier Document for the Continental stage, “is not to produce documents but to open horizons of hope for the fulfilment of the Church’s mission.”

The Instrumentum laboris is composed of an explanatory text and fifteen worksheets that reveal a dynamic vision of the concept of “synodality.” Specifically, there are main sections: Section A highlights the experience of the past two years and indicates a way forward to become an ever more synodal Church; Section B – entitled “Communion, Mission, Participation” – focuses on the “three priority issues” at the heart of the work to be done in October 2023. These are elaborated in three main themes: Growing in communion by welcoming everyone, excluding no one; recognizing and valuing the contribution of every baptised person in view of mission; and identifying governance structures and dynamics through which to articulate participation and authority over time in a missionary synodal Church.

“Rooted in this awareness,” the document affirms, “is the desire for a Church that is also increasingly synodal in its institutions, structures, and procedures.” It notes that a synodal Church is first and foremost a “Church of listening” and therefore “desires to be humble, and knows that it must ask forgiveness and has much to learn.” It continues, “The face of the Church today bears the signs of serious crises of mistrust and lack of credibility. In many contexts, crises related to sexual abuse, and abuse of power, money, and conscience have pushed the Church to undertake a demanding examination of conscience so that ‘moved by the Holy Spirit’ the Church ‘may never cease to renew herself’, in a journey of repentance and conversion that opens paths of reconciliation, healing, and justice.”

A synodal Church is also “a Church of encounter and dialogue” with believers of other religions and with other cultures and societies. It is a Church that “is not afraid of the variety it bears,” but on the contrary, “values it without forcing it into uniformity.” The Church is synodal when it is unceasingly nourished by the mystery it celebrates in the liturgy, during which it experiences everyday “radical unity” in the same prayer, in the midst of a “diversity” of languages and rites.

Other significant passages concern the question of authority (“Does authority arise as a form of power derived from the models offered by the world, or is it rooted in service?” is one of the questions); the need for “integral formation, initial and ongoing” for the People of God; as well as the need for “a similar effort” aimed at the renewal of the language used in the “liturgy, preaching, catechesis, sacred art, as well as in all forms of communication addressed to the Faithful and the wider public, including through new or traditional forms of media.” The renewal of language, the text states, must “aim to make these riches accessible and attractive to the men and women of our time, rather than an obstacle that keeps them at a distance.”

Read the Document Instrumentum Laboris in English.

Source: Vatican News

APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS POPE FRANCIS

TO THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO AND SOUTH SUDAN

(ECUMENICAL PEACE PILGRIMAGE TO SOUTH SUDAN)

[31 January - 5 February 2023]

MEETING WITH BISHOPS, PRIESTS, DEACONS, CONSECRATED PERSONS AND SEMINARIANS

ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS

Cathedral of Saint Therese (Juba)

Saturday, 4 February 2023

Dear brother Bishops, priests and deacons,

Dear consecrated brothers and sisters,

Dear seminarians, novices and aspirants, good morning to all of you!

I have been looking forward to meeting you, and I want to thank the Lord for this occasion. I am grateful to Bishop Tombe Trille for his words of greeting and to all of you for your presence today and also for your greeting; some of you travelled for days to be here today! Several of our previous experiences have a special place in my heart: the celebration in Saint Peter’s in 2017, when we prayed together for the gift of peace, and the spiritual retreat in 2019 with the political leaders, who were asked to embrace, through prayer, the firm resolve to pursue reconciliation and fraternity in this country. Indeed, all of us need to embrace Jesus, our peace and our hope.

In my address yesterday, I drew upon the image of the waters of the Nile, which flows through your country, as if it were its backbone. In the Bible, water is often associated with God’s activity in creation, his compassion in quenching our thirst when we wander through the desert, and his mercy in cleansing us when we are mired in sin. In baptism, he sanctified us “through the water of rebirth and renewal by the Holy Spirit” (Titus 3:5). From the same biblical perspective, I would like to take another look at the waters of the Nile. Merged with those waters are the tears of a people immersed in suffering and pain, and tormented by violence, who can pray like the psalmist, “By the rivers of Babylon—there we sat down and there we wept” (Ps 137:1). Indeed, the waters of that great river collect the sighs and sufferings of your communities, they collect the pain of so many shattered lives, they collect the tragedy of a people in flight, the sorrow and fear in the hearts and eyes of so many women and children. We can see this fear in the eyes of children. At the same time, though, the waters of the Nile remind us of the story of Moses and thus they also speak of liberation and salvation. From those waters, Moses was saved and, by leading his own people through the Red Sea, he became for them a means of liberation, an icon of the saving help of God who sees the affliction of his children, hears their cry and comes down to set them free (cf. Ex 3:7). Remembering the story of Moses, who led God’s people through the desert, let us ask ourselves what it means for us to be ministers of God in a land scarred by war, hatred, violence, and poverty. How can we exercise our ministry in this land, along the banks of a river bathed in so much innocent blood, among the tear-stained faces of the people entrusted to us? This is the question. And when I speak of ministry, I do so in the broad sense: priestly and diaconal ministry and also catechetical ministry, the ministry of teaching, which so many consecrated men and women, as well as the lay faithful, carry out.

To try to answer this, I would like to reflect on two aspects of Moses’ character: his meekness and his intercession. I think these two aspects concern our lives here.

The first thing that strikes us about the story of Moses is his meekness, his docile response to God’s initiative. We must not think, though, that it was always this way: at first, he attempted to fight injustice and oppression on his own. Saved by Pharaoh’s daughter in the waters of the Nile, he then discovered his identity and was moved by the suffering and humiliation of his brothers, so much so that one day he decided to take justice into his own hands: he killed an Egyptian who was beating a Hebrew. As a result, he had to flee to the desert, where he remained for many years. There he experienced a kind of interior desert. He had thought he could confront injustice on his own and now he found himself a fugitive, alone and in hiding, experiencing a bitter sense of failure. I wonder: What was Moses’ mistake? He had put himself at the centre, and relied on his strength alone. Yet in this way, he remained trapped in the worst of our human ways of doing things: he had responded to violence with violence.

At times, something similar can happen in our own lives as priests, deacons, religious, seminarians, consecrated men and women, all of us: deep down, we can think that we are at the centre of everything, that we can rely, if not in theory at least in practice, almost exclusively on our own talents and abilities. Or, as a Church, we think we can find an answer to people’s suffering and needs through human resources, like money, cleverness or power. Instead, everything we accomplish comes from God: he is the Lord, and we are called to be docile instruments in his hands. Moses learned this when, one day, God appeared to him “in a flame of fire out of a bush” (Ex 3:2). Moses found himself drawn to this sight; he was open to being amazed and so, in meekness, he approached that strange blazing fire. He thought: “I must turn aside and look at this great sight, and see why the bush is not burned up” (v. 3). This is the kind of meekness that we need in our ministry: a readiness to approach God in wonder and humility. Sisters and brothers, do not lose the wonder of the encounter with God! Do not lose the wonder of contact with the word of God. Moses let himself be drawn to God and guided by him. The primacy is not ours, the primacy is God’s: entrusting ourselves to his word before we start using our own words, meekly accepting his initiative before we get caught up in our personal and ecclesial projects.

By allowing ourselves, in meekness, to be shaped by the Lord, we experience renewal in our ministry. In the presence of the Good Shepherd, we realize that we are not tribal chieftains, but compassionate and merciful shepherds; not overlords, but servants who stoop to wash the feet of our brothers and sisters; we are not a worldly agency that administers earthly goods, but the community of God’s children. Dear sisters and brothers, let us do, then, what Moses did in God’s presence. Let us remove our sandals with humble awe (cf. v. 5) and divest ourselves of our human presumption. Let us allow ourselves to be drawn to the Lord and spend time with him in prayer. Let us daily approach the mystery of God, so that he can astonish us and burn away the dead wood of our pride and our immoderate ambitions, and make us humble travelling companions of all those entrusted to our care.

Purified and enlightened by the divine fire, Moses became a means of salvation for his suffering brothers and sisters. His meekness before God made him capable of interceding for them. This is the second aspect of his character that I would like to discuss today: Moses was an intercessor. He experienced a God of compassion, who hears the cry of his people and comes down to deliver them. This phrase is beautiful: he comes down. God comes down to deliver them. In his “condescension”, God comes down among us, even taking on our flesh in Jesus, experiencing our death and our most hellish moments. He constantly comes down in order to raise us up. Those who experience him are led to imitate him. Like Moses, who “came down” to be in the midst of his people a number of times during the sojourn in the desert. Indeed, at the most important and trying moments, he would ascend the mountain of God’s presence to intercede for the people, that is, to stand in their place in order to bring them closer to God, and then come down. Brothers and sisters, interceding “does not mean simply ‘praying for someone’, as we so often think. Etymologically it means ‘to step into the middle’, to be willing to walk into the middle of a situation” (C.M. MARTINI, Un grido di intercessione, Milan, 29 January 1991). Sometimes we do not obtain much, but we need to offer a cry of intercession. To intercede is thus to come down and place ourselves in the midst of our people, to act as a bridge that connects them to God.

It is precisely this art of “stepping into the middle” of our brothers and sisters that the Church’s pastors need to cultivate; this must be their specialty: the ability to step into the middle of their sufferings and tears, into the middle of their hunger for God and their thirst for love. Our first duty is not to be a Church that is perfectly organized – any company can do this – but a Church that, in the name of Christ, stands in the midst of people’s troubled lives, a Church that is willing to dirty its hands for people. We must never exercise our ministry by chasing after religious or social prestige – the ugliness of careerism – but rather by walking in the midst of and alongside our people, learning to listen and to dialogue, cooperating as ministers with one another and with the laity. Let me repeat this important word: together. Let us never forget it: together. Bishops and priests, priests and deacons, pastors and seminarians, ordained ministers and religious – always showing respect for the marvelous specificity of religious life. Let us make every effort to banish the temptation to individualism, to partisan interests. How sad it is when the Church’s pastors are incapable of communion, when they fail to cooperate, and even ignore one another! Let us cultivate mutual respect, closeness and practical cooperation. If we fail to do this ourselves, how can we preach it to others?

Let us now go back to Moses, and reflect on the art of intercession, let us look at his hands. Scripture offers us three images in this regard: Moses with staff in hand, Moses with outstretched hands, Moses with his hands raised to heaven.

The first image, Moses with staff in hand, tells us that he intercedes with prophecy. With that staff, he works wonders, signs of God’s presence and power; he speaks in God’s name, forcefully denouncing the oppression that the people are suffering, and demanding Pharaoh to let them depart. Brothers and sisters, we too are called to intercede for our people, to raise our voices against the injustice and the abuses of power that oppress and use violence to suit their own ends amid the cloud of conflicts. If we want to be pastors who intercede, we cannot remain neutral before the pain caused by acts of injustice and violence. To violate the fundamental rights of any woman or man is an offence against Christ himself. I was happy to hear in Father Luka’s testimony that the Church tirelessly carries out a ministry that is both prophetic and pastoral. Thank you! Thank you because, if there is one temptation against which we must guard, it is that of leaving things as they are and not getting involved in situations for fear of losing privileges and benefits.

The second image is that of Moses with outstretched hands. Scripture tells us that he “stretched out his hand over the sea” (Ex 14:21). His extended hands are the sign that God is about to show his power. Later, Moses will hold the tablets of the Law in his hands (cf. Ex 34:29) and show them to the people; his upraised hands demonstrate the closeness of God who is ever active in accompanying his people. Of itself, prophecy does not suffice for deliverance from evil: it is necessary to extend our arms to our brothers and sisters, to support them on their journey; to caress God’s flock. We can imagine Moses pointing the way and taking people by the hand to encourage them to persevere. For forty years, in his old age, he remained at their side: that is what closeness means. It was no easy task: often he had to lift the spirits of a people who were discouraged and weary, hungry and thirsty, and sometimes even wayward and prone to grumbling and lethargy. In doing so, Moses also had to struggle with himself, for at times, he too experienced moments of darkness and desolation, as when he said to the Lord: “Why have you treated your servant so badly? Why have I not found favour in your sight, that you lay the burden of all this people on me? … I am not able to carry all this people alone, for they are too heavy for me” (Num 11:11, 14). Look at how Moses prayed: he was tired. Yet, he did not step back: ever close to God, he did not turn his back on his people. This is also our job: to stretch out our hands, to rouse our brothers and sisters, to remind them that God is faithful to his promises, to urge them on. Our hands were “anointed with Spirit” not only for the sacred rites, but also to encourage, help and accompany people to leave behind whatever paralyzes them, keeps them closed in on themselves, and makes them fearful.

Finally – the third image – Moses with his hands raised to heaven. When the people fell into sin and made a golden calf for themselves, Moses went up the mountain once again – think of what great patience he must have had! – and said a prayer, which shows him wrestling with God, begging him not to abandon Israel. He went so far as to say: “This people has sinned a great sin; they have made for themselves gods of gold. But now, if you will only forgive their sin – but if not, blot me out of the book that you have written” (Ex 32:31-32). Moses stood with the people to the very end, raising his hands on their behalf. He did not think of saving himself alone; he did not sell out the people for his own interests! He interceded, he wrestled with God; he kept his arms raised in prayer while his brethren battled in the valley below (cf. Ex 17:8-16). Bringing the struggles of the people before God in prayer, obtaining forgiveness for them, administering reconciliation as channels of God’s mercy: this is our task as intercessors.

Beloved, these prophetic hands, outstretched and raised, demand great effort, which is not easy. To be prophets, companions and intercessors, to show with our life the mystery of God’s closeness to his people, can cost us our lives. Many priests and religious – as Sister Regina told us of her own sisters – have been victims of violence and attacks in which they lost their lives. In a very real way, they offered their lives for the sake of the Gospel. Their closeness to their brothers and sisters is a marvellous testimony that they bequeath to us, a legacy that invites us to carry forward their mission. Let us think of Saint Daniele Comboni, who with his missionary brothers carried out a great work of evangelization in this land. He used to say that a missionary must be ready to do anything for the sake of Christ and the Gospel. We need courageous and generous souls ready to suffer and die for Africa.

I would like to thank you, then, for everything that you do amid so many trials and tribulations. Thank you, on behalf of the entire Church, for your dedication, your courage, your sacrifices and your patience. Thank you! Dear brothers and sisters, I pray that you will always be generous pastors and witnesses, armed only with prayer and love; pastors and witnesses allowing yourselves, in meekness, to be constantly surprised by God’s grace; and that you may become a means of salvation for others, pastors and prophets of closeness who accompany the people, intercessors with uplifted arms. May the Blessed Virgin Mary protect you. At this moment, let us recall in silence those brothers and sisters of ours who have given their lives in pastoral ministry here, and let us thank the Lord because he has been close. Let us thank the Lord for the closeness of their “martyrdom”. Let us pray in silence.

Thank you for your witness. And, if you have a little time, please pray for me. Thank you.

On Tuesday morning, October 4, feast of St. Francis of Assisi, a press conference on the premiere of The Letter was held in the Vatican’s Sala Stampa. The film tells the story of various frontline leaders’ journeys to Rome to discuss the encyclical Laudato Si’ with Pope Francis.

The press conference was addressed by Cardinal Michael Czerny, Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development; Dr. Hoesung Lee, Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cacique Odair “Dadá” Borari, a protagonist of the film and Chief-General of the Maró Indigenous Territory, Pará, Brazil; Dr. Lorna Gold, President of the Board, Laudato Si’ Movement; and Nicolas Brown, Writer and Director of The Letter, all presented by Matteo Bruni, Director of the Holy See Press Office.

Card. Michael Czerny, said: “The great treasure of Laudato Si’s wisdom needs to become far more deeply known and effectively put into practice,” referring to the fact that, seven years after the encyclical’s launch, its message is still not known and the environmental crisis of our common home has worsened drastically.

The cardinal explained the meaning of the film’s title: “Our Dicastery sent a letter to the film’s protagonists inviting them to meet the Holy Father for a dialogue with him. So, the film ‘The Letter’ highlights the key concept of dialogue.” But he added: “For this dialogue to be authentic, all voices should be heard.”

“This beautiful film – a heartbreaking yet hopeful story – is a clarion cry to people everywhere: wake up! get serious! act together! act now!”, concluded Czerny.

The Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Dr. Hoesung Lee, began by saying: “Today is a special day for the alliance between science and faith,” because, in addition to celebrating the premiere of ‘The Letter’, “the Holy See’s official entry into the Paris Agreement on climate change comes into effect today.”

“Humanity is at a crossroads,” he said. “Both the science community and the faith community are clear: the planet is in crisis and its life-support systems are in peril. The stakes have never been higher. May the world receive this “Letter” with an open heart and open mind.”

Meanwhile, the director of The Letter, Nicolas Brown, thanked his colleagues and all those involved in the film, in particular the four voices involved in the film: “These voices are on the front lines, and they are the most experienced to tell us the reality of what is happening in relation to the climate crisis,” from a different perspective than the scientific community.

Following this, one of the protagonists of the film spoke, Cacique Odair “Dadá” Borari: “I am here once again to speak on behalf of the forest and the Indigenous population. We do not want to see the Amazon forest finished, because life is in it”. The cacique affirmed that he suffered the consequences of defending the Amazon and asked the presidents to listen to this message: “The forest is asking for help, and to keep it alive, it does not depend only on the Indigenous people, but on everyone, especially the government. Let’s unite to protect it.”

When asked about his expectations for the elections in Brazil, he said: “We hope that the new president will think about the Amazon and new policies for the development of Brazil.”

Representing Laudato Si’ Movement and as a participant of the film, Lorna Gold explained that “the essence of this film is to bring this wonderful book to new audiences,” responding to Pope Francis’ intention in writing Laudato Si’. “But we know that not all people have read it, so how do we reach them? That’s how the idea of making a documentary film came to us.”

“When we asked Nicolas to help us make a film about Laudato Si’, he said, “But…there is no plot.” That’s why Gold highlighted Off the Fence’s work to tell this story: “The only way to tell the story of Laudato Si’ is to get inside it. This is a film about the dialogue between various voices and how to act together for the common home.”

“It is not a coincidence that this film is being released on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi. The film calls everyone to change our hearts and this is the main message: we need to develop the ability to care for each other.”

“How do we overcome the ‘resistance’ in our communities to carry the right Laudato Si’ message?” a journalist asked the panel. “The Laudato Si’ Movement has more than 900 organizations as allies to help us carry the message,” said Lorna Gold. And Card. Czerny added, “The key is conversion of heart, and I am very hopeful about that.”

WATCH: The full movie today in YouTube Originals

About The Letter: The film, produced by Oscar-winning producers Off the Fence (My Octopus Teacher) explores issues including Indigenous rights, climate migration, and youth leadership in the context of action on climate and nature. The highlight of the film is the exclusive dialogue that the protagonists have with Pope Francis.

Source: https://laudatosimovement.org/

From September 22 to 24, economic scholars, enterpreneurs and change makers from more than 100 countriES Aaround the world met in Assisi for the event The Economy of Francesco.

The September 2022 event represented the first in-person meeting for young people called by Pope Francis to give a soul to the economy. The meeting saw young people who have been actively working in these past months, along with new young people, who have a desire to contribute to a new season of economic thought and practice.

Pope Francis calls on the young people of the Economy of Francesco to work for social, relational and spiritual sustainability, and to recognize the cry of the poor and the cry of the planet.

ADDRESS OF HIS HOLYNESS POPE FRANCIS

PalaEventi Santa Maria degli Angeli (Assisi)

Saturday, 24 September 2022

Dear young people, good morning!

I greet all those who are able to be here today. I would also like to greet those who could not make it, those at home. I greet all of you! We are all united: those joining us from various places and those present here.

I have waited more than three years for this moment, since 1 May 2019, when I wrote you the letter that called and then brought you here to Assisi. For many of you – as we have just heard – the encounter with the Economy of Francesco awakened something that was already within you. You were already committed to creating a new economy; my letter brought you together, gave you a broader horizon and made you feel part of a worldwide community of young people who have the same vocation. When a young person sees in another young person the same calling, and this experience is repeated with hundreds, even thousands of other young people, then great things become possible, even the hope of changing an enormous and complex system like the world economy. Indeed, it would appear that talking about economics today seems like an old thing: today we talk about finance, and finance is a watery thing, a gaseous thing, you cannot hold it. Once, a good world economist told me that she attended a conference on the link between economics, humanism and religion. The event went well. She wanted to do the same with finance and was not able to do so. Beware of this fleeting nature of finances: you must resume economic activity from the roots, from human roots as was done in the past. You young people, with the help of God, know what to do, you can do it; young people have done many things before in the course of history.

You are living your youth in a time that is not easy: the environmental crisis, then the pandemic, and now the war in Ukraine, and the other wars which have continued for years in various countries, have marked your lives. Our generation has left you with a rich heritage, but we have not known how to protect the planet and are not securing peace. When you hear that the fishermen of San Benedetto del Tronto, pulled 12 tons of dirt and plastic and other things out of the sea in one year, you realise that we do not know how to protect the environment. Nor do we know how to keep peace as a result. You are called to become artisans and builders of our common home, a common home that “is falling into ruin”. Today, a new economy inspired by Francis of Assisi can and must become an economy of friendship with the earth and an economy of peace. It is a question of transforming an economy that kills (cf. Evangelii Gaudium, 53) into an economy of life, in all its aspects. That “good life” is not the sweet life or living it well, no. Good living is the mysticism that the indigenous peoples teach us to have in relation to the earth.

I admire your decision to model this gathering in Assisi on prophecy. I liked what you said about prophecy. After his conversion, Francis of Assisi’s life was a prophecy that continues also into our own times. In the Bible, prophecy is very much connected with young people. Samuel was called as a boy, Jeremiah and Ezechiel were young, Daniel was a youth when he prophesied the innocence of Susanna and saved her from death (cf. Dan 13:45-50); and the prophet Joel announced to the people that God would send his Spirit and “their sons and daughters would prophesy” (3:1). According to Scripture, young people are the bearers of a spirit of knowledge and intelligence. It was the young David who humbled the arrogance of the giant Goliath (cf 1 Sam 17: 49-51). Indeed, when civil society and businesses lack the skills of the young, the whole of society withers and the life of everyone is extinguished. There is a lack of creativity, optimism, enthusiasm, and courage to take risks. A society and an economy without young people are sad, pessimistic and cynical. If you want to see this, go to these ultra-specialized universities in liberal economics, and look at the faces of the young men and women studying there. Yet, we are grateful to God that you are here: not only will you be there tomorrow, you are here today. You are not just the “not yet”, you are also the “already here”, you are the present.

An economy that inspires us with the prophetic dimension is expressed today in a new vision of the environment and the earth. We have to embrace this harmony with the environment and the earth. There are many people, businesses and institutions that are making an ecological conversion. We need to go forward on this road and do more. You are doing and asking everyone to do this “more”. It is not enough to make cosmetic changes; we need to discuss models of development. The situation is such that we cannot just wait until the next international summit, which might be too late. The earth burns today, and today we must change, at all levels. In this last year, you have worked on the economy of plants, an innovative topic. You have seen that the plant paradigm contains a different approach to the earth and the environment. Plants cooperate with their whole environmental surroundings, and also when they compete, they actually are cooperating for the good of the ecosystem. Let us learn from the meekness of plants: their humility and their silence can offer us a different approach, which we urgently need. For, if we speak of ecological transition but remain in the economic paradigm of the twentieth century, which plundered the earth and its natural resources, then the strategies we adopt will always be insufficient or sick from the roots. The Bible is full of images of trees and plants, from the tree of life to the mustard seed. And Saint Francis helps us with his universal fraternity with all living creatures. We human beings, in these last two centuries, have grown at the expense of the earth. The earth is the one that pays the price. We have often plundered in order to increase our own well-being, and not even the well-being of all, but of a small group. Now is the time for new courage in abandoning fossil fuels to accelerate the development of zero or positive impact sources of energy.

We must also accept the universal ethical principal – however unpopular – that damages must be repaired. This is a universal, ethical principle: damage must be repaired. If we grew up abusing the planet and the atmosphere, today we must also learn to make sacrifices in lifestyles that remain unsustainable. Otherwise, our children and grandchildren will pay the price, a price that will be too high and too unjust. Six months ago, I listened to a very important scientist, who said: “Yesterday my granddaughter was born. If we continue like this, within thirty years the poor girl will have to live in an uninhabitable world”. Our children and grandchildren will pay the price, a price that will be very high and unfair. Quick and decisive change is needed. I say this with seriousness. I am counting on you! Please, do not be afraid to bother us! Be an example for us! And I tell you the truth: one needs courage to walk on this path, and sometimes it takes a little bit of heroism. In a meeting, I listened to a 25-year-old man, who had just graduated as an engineer, and who could not find a job. In the end, he found one in an industry about which he did not know much. When he realised what the job entailed, he refused it because they were making weapons. These are the heroes of today.

Sustainability, then, is a multidimensional word. Aside from the environmental, there are also the social, relational and spiritual dimensions. The social aspect is slowly beginning to be recognized: we are realizing that the cry of the poor and the cry of the earth are the same cry (cf. Laudato Si’, 49). When we work for ecological transformation, then, we must keep in mind the effects that some environmental choices have on poverty. Not all environmental solutions have the same effects on the poorest, and therefore those that reduce misery and inequality should be preferred. As we seek to save the planet, we must not neglect those who suffer. Carbon dioxide is not the only pollution that kills; inequality also fatally damages our planet. We must not allow the new environmental calamities to erase from public view the long-standing and ever-present calamities of social injustice, as well as political injustices. Let us think, for example, of a political injustice; the poor battered people of the Rohingya who wander from one place to another because they cannot live in their own homeland. It is a political injustice.

Then there is the unsustainability of our relationships: in many countries relationships between people are becoming impoverished. Especially in the West, communities are becoming increasingly fragile and fragmented. The family, and with it the acceptance and protection of life, is suffering a serious crisis in some regions of the world. Current consumerism seeks to fill the void of human relationships with ever more sophisticated commodities – loneliness is big business in our time! – but in this way it generates a famine of happiness. This is not a good thing. Think of the demographic winter, for example, and how it relates to all this. The demographic winter where the population of all countries is going down significantly because, instead of having children, people give greater attention to having emotional relationships with dogs and cats. We have to start procreating again. But also in this demographic winter there is the slavery of women: a woman who cannot be a mother because as soon as her belly begins to rise, they fire her; pregnant women are not always allowed to work.

Finally, there is a spiritual unsustainability to our capitalism. Human beings, created in the image and likeness of God, are seekers of meaning before being seekers of material goods. We are all seekers of meaning. That is why the first capital of any society is spiritual capital, for this is what gives us a reason to get up every morning and go to work, and engenders the joy of living that is also necessary for the economy. Our world is quickly consuming this essential kind of capital, accumulated over centuries by religions, wise traditions and popular piety. Consequently, young people especially suffer from this lack of meaning: faced with the pain and uncertainties of life, they often find their souls depleted of the spiritual resources needed to process suffering, frustration, disappointment and grief. Go and look at the percentage of suicide among young people, and how the numbers are going up. They do even not publish everything, and sometimes hide the figures. The fragility of many young people comes from a lack of this precious spiritual capital – an invisible but more real capital than financial or technological capital. I ask, do you have a spiritual capital? Everyone can answer quietly.We urgently need to rebuild this essential spiritual patrimony. Technology can do much: it teaches us the “what” and the “how”: but it does not tell us the “why”; and so our actions become sterile and do not bring fulfilment to life, not even economic life.

Finding myself in the city of Francis, I cannot help but speak about poverty. Developing an economy inspired by him means committing ourselves to putting the poor at the centre. Starting with them, we look at the economy; starting with them, we look at the world. There is no “Economy of Francesco” without respect, care and love for the poor, for every poor person, for every fragile and vulnerable person – from conception in the womb to the sick person with disabilities, to the elderly person in difficulty. I would go even further: an economy of Francesco must not limit itself to working for or with the poor. As long as our system “produces” discarded people, and we operate according to this system, we will be accomplices of an economy that kills. Let us ask ourselves. Are we doing enough to change this economy or are we content with painting a house in order to change its colour without changing the structure of the house? It is not a question of paint strokes, no: you have to change the structure. Perhaps our response should not be based on how much we can do but on how we are able to open new paths so that the poor themselves can become protagonists of change.In this regard, there are significant and developed examples in India and the Philippines.

Saint Francis loved not only the poor but poverty itself. This can also be called an austere way of living. Francis went to lepers not so much to love them but because he wanted to become poor like them. Following Jesus Christ, he stripped himself of everything to become poor with the poor. Indeed, the first market economy was born in the thirteenth century in Europe through daily contact with Franciscan Friars, who were friends of the first merchants. That economy certainly created wealth but it did not despise poverty. Our capitalism, instead, wants to help the poor but does not respect them; it does not understand the paradox in the beatitude: “Blessed are the poor” (cf. Lk 6:20). We do not have to love poverty. On the contrary, we need to combat it, above all, by creating work, dignified work. The Gospel tells us, however, that without respect for the poor, we cannot combat poverty. It is from here that all of us need to begin, including entrepreneurs and economists: living the evangelical paradoxes of Francis. When I talk to people or hear confessions, I always ask: “Do you give alms to the poor?” – “Yes, yes, yes!” – “And when you give alms to the poor, do you look him or her in the eye?” – “Eh, I don’t know ...” – “And when you give alms, do you throw the coin or touch the poor person’s hand?”.They do not look at the eyes and do not touch; and this is a way of distancing ourselves from the spirit of poverty, distancing ourselves from the true reality of the poor, distancing ourselves from the humanity that every human relationship must have. Someone will say to me: “Holy Father, we haven’t got much time, when are you finishing?”: I am finishing now.

In light of this reflection, I would like to leave you with three signposts for moving forward.

The first is to look at the world with the eyes of the poorest of the poor. In the medieval period, the Franciscan movement was able to create the first economic theories and even the first banks for those in need (“Monti di Pietà”), because it looked at the world with the eyes of the poorest of the poor. You too will improve the economy if you look at things from the perspective of victims and the discarded. In order to have the eyes of the poor and victims, however, it is necessary to get to know them, to be their friends. And, believe me, if you become friends of the poor, you will share their life, you will have a share in the Kingdom of God, because Jesus said that to these belong the Kingdom of God. For this reason, they are blessed (cf. Lk 6:20). I will say it again: may your daily choices not “produce” discarded people.

The second: you are mostly students, scholars and entrepreneurs, but do not forget about work, do not forget about workers. The work of our hands. Work is already the challenge of our time, and it will be all the more the challenge of tomorrow. Without dignified work and just remuneration, young people will not truly become adults and inequality will increase. It is possible, at times, for a person to survive without work but he or she does not live well. So while you create goods and services, do not forget to create work, good work and work for everyone.

The third signpost is incarnation. In the crucial moments of history, those who left a good mark were able to do so because they translated ideals, desires and values into concrete actions. They “incarnated” them. In addition to writing and organizing conferences, these men and women established schools and universities, banks, trade unions, associations and institutions. You will change the economic world if you use your hands together with your heart and head. The three languages. When we think: we have the head, the language of thought. But we don’t stop there, we have to combine it with the language of feeling, the language of the heart. And not only that, we also have to link it with the language of the hands. So you have to do what you feel and think, feel what you do, and think what you feel and do. This is the union of the three languages. Ideas are necessary, they entice us, especially young people, but they can turn into traps if they do not become “flesh”, in other words something concrete, a daily commitment: the three languages. Ideas alone do not work; we will all finish up in an endless circle if we follow just ideas. Ideas are necessary, but they must take “flesh”. The Church has always rejected the gnostic – gnosis, that of idea alone – temptation of thinking that the world changes only through different knowledge, without the effort of the flesh. Actions are less “luminous” than great ideas because they are concrete, particular, limited, with light and shadow together, but they fertilize the ground day after day for reality is greater than an idea (cf. Evangelii Gaudium, 233). Dear young people, reality is always bigger than idea: pay attention to this.

Dear brothers and sisters, I thank you for your efforts: thank you. Go forward together with the inspiration and intercession of Saint Francis. And if you are agreeable, I would like to conclude with a prayer. I will pray it aloud and you can follow me silently in your heart.

Father, we ask forgiveness for having damaged the earth, for not having respected indigenous cultures, for not having valued and loved the poorest of the poor, for having created wealth without communion. Living God, who with your Spirit have inspired the hearts, hands and minds of these young people and sent them on the way to a promised land, look kindly on their generosity, love and desire to spend their lives for a great ideal. Bless them, Father, in their undertakings, studies and dreams; accompany them in their difficulties and sufferings, help them to transform their difficulties and sufferings into virtue and wisdom. Support their longing for the good and for life, lift them up when facing disappointments due to bad examples, do let them become discouraged but instead may they continue on their path. You, whose only begotten Son became a carpenter, grant them the joy of transforming the world with love, ingenuity and hands. Amen.

Thank you very much.

Pope Francis

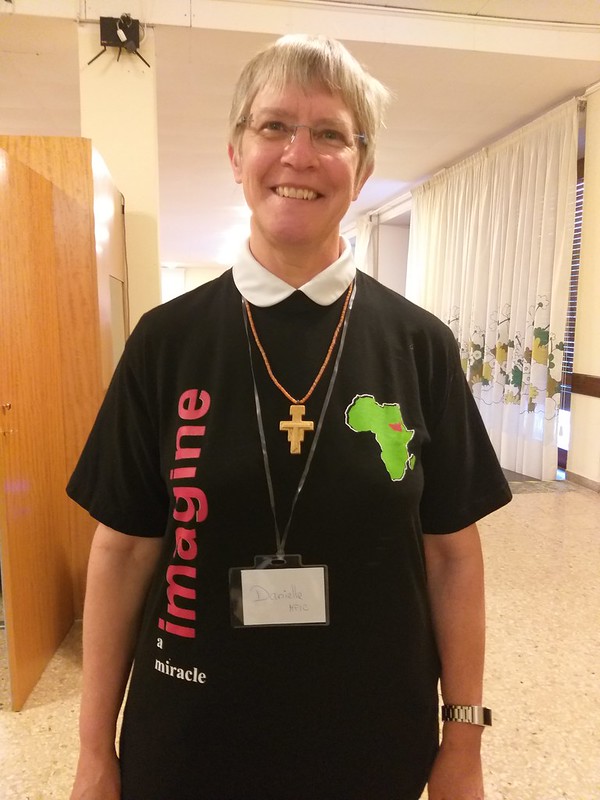

On January 9th and 10th 2020 Sister Danielle participated in the Annual ROME CONSTELLATION’S ASSEMBLY of UISG International Union of Superiors General.

On January 9th and 10th 2020 Sister Danielle participated in the Annual ROME CONSTELLATION’S ASSEMBLY of UISG International Union of Superiors General.

In communion with the Church, that is living intensely the extraordinary Missionary Month and the Synod of Amazonia, the Constellation Committee of Rome, the most international of all constellations, celebrated its annual Assembly and invited all the General Superiors of the Constellation to participate in this meeting, which is always an opportunity to learn, share and strengthen our identity as women consecrated in the Church, welcoming the challenges that arise in our Institutes today.

This meeting was also the opportunity to speak about the MFIC and our commitment with Solidarity with South Sudan.